In Eastern Christianity, the icon is an important object used to depict divine realities that would otherwise be inexpressible. The original Byzantine style of iconography which serves as the basis and inspiration for Eastern icons today, and Ukrainian icons specifically, began developing in full force during the first half of the IVth century. Ukrainian iconography specifically can be traced back at least as early as 988, when Volodymyr the Great first officially baptized Kyivan Rus, which later became Ukraine. Iconography from this era is known as Princely or Kyivan Iconography. This era in Ukrainian iconography most closely reflects the Greek and Byzantine style, as many icons were actually commissioned by Volodymyr the Great from Byzantium.

The oldest existing examples of Ukrainian icons are from the XIVth century. Previous to this time, the geopolitical situation in Kyivan Rus was incredibly unstable, and icons were often moved from place to place as loot and symbols of conquest. The Mongol invasion and sacking of Kyiv in 1240 especially resulted in the destruction of most Ukrainian icons made up to that point (Hordynsky, 11). The Galician iconographic style that started at that point is an example of a form of uniquely Ukrainian iconography that still persists today, with a much greater number of surviving icons allowing for more in-depth study and appreciation (Hordynsky, 11). The Galician style of iconography built directly on the iconography of the Princely era, but diverged increasingly from the Greek-Byzantine style.

The Galician style of iconography built directly on the iconography of the Princely era, but diverged increasingly from the Greek-Byzantine style. The Galician area is today’s Western Ukraine, but does not match up directly with current borders. Elements of the Galician school of iconography can therefore be seen in Polish, Lithunian, and other art from the surrounding area (Horodynsky, 11).

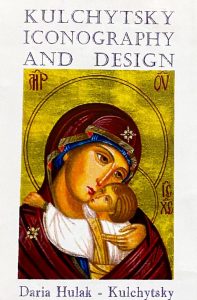

Despite great growth in interest and respect of iconography going into the mid-19th century, as both a religious and cultural treasure and a skilled art, the Bolshevik revolution and Ukraine’s time as part of the Soviet Union resulted in the destruction and liquidation of icons and other items of religious and cultural importance. From the first days of the Bolshevik revolution to the last days of the Soviet Union, the Soviet regime viciously destroyed or sold off religious objects. The greater the monetary or artistic worth of the object, the more likely the Bolsheviks were to seize and sell it. The plunder of churches was widespread, and icons were seized in great numbers. In some villages there were even mass burning of icons and other religious objects, in an effort to discredit Christianity in the eyes of the Ukrainian people (Bilokin, 27-30). Because of the unwelcoming environment for iconography in Ukraine, much development of Ukrainian iconography during the time of the Soviet Union happened abroad in the Ukrainian diaspora in countries such as Canada and the United States. Daria Hulak-Kulchytska is one such Ukrainian iconographer, based in Cleveland, Ohio, who has helped keep the art of Ukrainian iconography alive and developing through her work.

The specific iconographic style that Daria Hulak-Kulchytsky believes best represents the Ukrainian icon, and which she herself follows, is the Halytsko-Volynsky style. The Halytsko-Volynsky region of Ukraine includes the region of Halychyna, and so the iconographic style is that of the Galician icon. Many of the most easily noticeable differences between Greek and Ukrainian iconography are a result of the different environments that the people lived in. Greek icons, for example, feature darker features compared to Ukrainian icons, which is a reflection of the warmer climate in Greece.

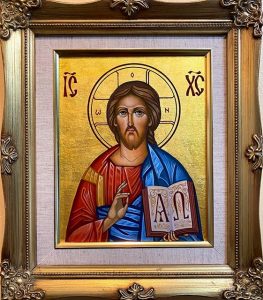

Three icons by Daria Hulak-Kulchytsky are on display at the Ukrainian Museum-Archives, in the front room of the museum. Two of these icons are more traditional in composition and type, one being of Jesus, and one of Mary holding the baby Jesus. The third is a more modern composition, once again of Mary holding the baby Jesus, but this time with more uniquely Ukrainian aspects, including traditional Ukrainian embroidered clothes, called vyshyvanka.

The more traditional of the icons with Mary holding baby Jesus shows an image of great love and tenderness between a mother and her child. Unlike some icons in the past, which often depicted more strict images of Mary and Jesus, the love and care that Mrs. Kulchytsky painted into this icon shows the humanity as well as divinity of the figures. Traditionally icons are never signed, because icons, as Mrs. Kulchytsky described, are “for the glory of God, and not for the glory of the artists.” However, after having her work plagiarized many times, Mrs. Kulchytska was advised to somehow indicate the originality of her work, and now marks her initials, DHK, somewhere on the icon.

When asked why she thinks her icons are so well received and even copied or plagiarized, Mrs. Kulchytsky commented that she believes that her icons answer a need that people have, as the viewer is able to feel the love that is portrayed, and to see the distinctly Ukrainian features and composition.

The more modern icon of Mary holding baby Jesus is one in Daria Hulak-Kulchytsky’s collection of Ukrainian madonnas. After seeing an icon of Mary in traditional Armenian clothes at an Armenian Orthodox church where she had been commissioned to work early on in her career as an iconographer, she asked the priest about the decision to depict Mary in traditional Armenian dress, to which he replied that it was to show that it’s “because she’s ours” (Hulak-Kulchytsky). The comment really struck Mrs. Kulchytsky, and ever since then she has painted many icons of Ukrainian madonnas dressed in traditional Ukrainian clothes from various regions of Ukraine. Mrs. Kulchtsky calls the icon at the UMA the “Madonna in Black,” because of the dark colors of the vyshyvanka and starker overall composition. This specific icon represents the Holodomor, the planned starvation and genocide of the Ukrainian people by Stalin in 1932-1933, with sad expressions on Mary and Jesus, who are dressed in clothes from the Poltava region in Ukraine, the area where some of the worst hunger was (Hulak-Kulchytsky).

Ukrainian iconography, whether by iconographers within Ukraine or in the Ukrainian diaspora, is both a unique and vibrant artform, as well as a form of prayer and worship, and a form of artistic and cultural expression. In the face of intense pressure and persecution, the practice of Ukrainian iconography has persisted and flourished, and continues to grow in importance even today. The icons on exhibit at the Ukrainian Museum-Archives, and the work that Daria Hulak-Kulchytsky and other iconographers like her do, helps to preserve the history of iconography, making it accessible to the younger generation and encouraging the continued study and respect of Ukrainian iconography and icons.

Text written by Anastasia Matuszak, University of Notre Dame.

Works Cited

Bilokin, Serhii. “A History of the Destruction and Preservation of Cultural Treasures.” Ukrainian Sculptures and Icons A History of Their Rescue Exhibition Catalogue from the collections of the President of Ukraine, Victor Yushchenko, and the collections of Petro Honchar, Ihor Hryniv, Volodymyr Koziuk, Vasyl Vovku, and Lidia Lykhach. RODOVID PRESS, Kyiv, Ukraine, 2006.

Hordynsky, Sviatoslav. The Ukrainian Icon of the XIIth to XVIIIth Centuries. Translated by Walter Dushnick, Providence Association of Ukrainian Catholics in America, Philadelphia, PA, 1973.

Hulak-Kulchytsky, Daria. Interview with Daria Hulak-Kulchytsky. July 3, 2021.

Icons of Ukraine Commemorating the Millennium of Christianity 988-1988. Chopivsky Family Foundation, 1988.